Obviousness and the Patent Office’s Burden to Explain, Part II: Trouble with Phonons

Jun 12th, 2017 by Jon Schuchardt | News | Recent News & Articles |

In a memorable Star Trek episode, Captain Kirk and crew have trouble with “tribbles,” irresistible critters that seem like ideal pets until their propensity to devour grains and multiply becomes apparent.

In Rovalma S.A. v. Böhler-Edelstahl GmbH & Co. KG (decided May 11, 2017), the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) recently had trouble with “phonons” and struggled to adequately explain why Rovalma’s phonon-laced process would have been obvious. The Federal Circuit concluded that the lack of a reasoned explanation warranted a remand. The decision continues a trend, discussed in our earlier article, in which the Federal Circuit insists on reasoned explanations rather than conclusory assertions of obviousness.

“What’s a phonon?” you might reasonably ask. I did. Without getting into messy math that would have baffled me on my best grad school days, “phonon” refers to a collective excitation in a periodic, elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter, especially solids. Apparently, understanding phonons can help us better appreciate thermal conductivity of metals.

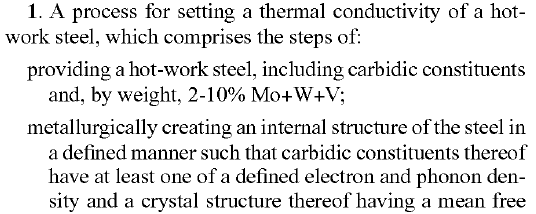

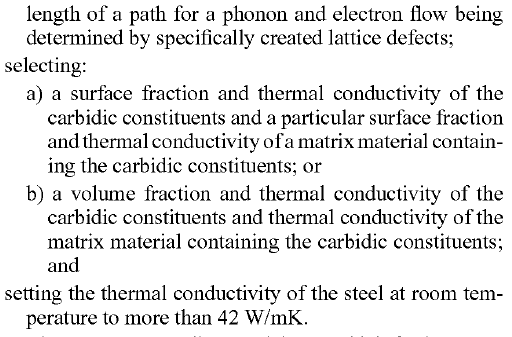

Claim 1 from Rovalma’s U.S. Pat. No. 8,557,056 reads as follows:

In its petition for inter partes review (IPR), Böhler argued that the process steps of “providing,” “creating,” “selecting,” and “setting” should be interpreted to cover specific chemical compositions regardless of how one arrives at the compositions. The Board adopted Böhler’s proposed claim construction, concluded that Böhler was reasonably likely to prevail on its obviousness assertion, and instituted IPR.

Rovalma argued that the claim construction proposed by Böhler was incorrect, i.e., that the claim should be construed to require performance of the recited process steps. Rovalma presented extrinsic evidence to bolster an argument that its claims were enabled by the disclosure. According to Rovalma, a skilled person could have predicted the formation of certain carbides based on particular heat treatments, could have used available software to perform necessary calculations, and would have understood that thermal conductivity for steel depends on lattice defects and impurities.

For its final written decision, the Board adopted Rovalma’s claim construction but concluded that the claims would have been obvious, relying largely on Rovalma’s literature submissions. The Board found that a person of ordinary skill “would have recognized that thermal processing conditions affect internal structure and, thus, thermal properties of steel.” The Board summarily concluded that a skilled person would have increased the thermal conductivity of steel and would have had a reasonable expectation of success in doing achieving higher thermal conductivity based on prior art.

On appeal to the Federal Circuit, Rovalma argued both evidentiary insufficiency and procedural inadequacy. The Federal Circuit sided with Rovalma on both grounds. Here, we discuss only the argument related to evidentiary insufficiency.

Specifically, Rovalma argued that the Board failed to justify its factual findings that a person of ordinary skill (1) would have appreciated that the claimed thermal conductivities could be achieved by practicing the claimed process steps; (2) would have been motivated to increase the thermal conductivities of the steels; and (3) would have had a reasonable expectation of success in achieving the claimed thermal conductivities.

The Federal Circuit held that the Board “did not sufficiently explain the basis for its obviousness determinations to permit us to resolve the substantial-evidence issues raised by Rovalma.” According to the court, “[w]e have repeatedly insisted on such [explicit] explanations in reviewing the adequacy of the Board’s analysis—both as a matter of obviousness law and administrative law.” The Board concluded that the claimed process steps were either inherent or obvious from Rovalma’s art submissions, but the Board did not explain the evidentiary basis for its determinations. “Nor did the Board adequately explain why a person of ordinary skill in the art would have been motivated to increase the thermal conductivities of the steels disclosed in the prior art.” The court found that adequate explanation was also “lacking” for why a skilled person would have reasonably expected success in achieving higher thermal conductivities. The court concluded that the Board’s failure to create a record that could be reviewed required a remand.

Rovalma continues a trend that has been percolating at the Federal Circuit in recent months; see also: In re NuVasive, Inc. (decided December 7, 2016), In re Van Os (decided January 3, 2017), Personal Web Technologies v. Apple (decided February 14, 2017), and Icon Health & Fitness v. Strava (decided February 27, 2017). The court now appears more willing to delve into the nitty gritty of whether the Board has made thorough, reasoned explanations based on good evidence regarding motivation to modify or combine reference teachings and regarding the separate and distinct requirement of a reasonable expectation of success (see Judge O’Malley’s opinion in Intelligent Bio-Systems v. Illumina Cambridge, decided May 9, 2016).

I’m no metallurgy expert, but I sympathize with Böhler. The process language of the ‘056 patent is ill-defined and wishy-washy. We start with a known composition: steel containing molybdenum, tungsten, and vanadium. Just how do we know when we’ve managed to create a steel structure “such that carbidic constituents thereof have . . . a defined electron and phonon density”? How do we know when “the mean free length of a path for a phonon and electron flow” is “determined by specifically created lattice defects”? How, exactly, is the steel composition modified to achieve these characteristics? The other process requisites are no more illuminating. On remand, Rovalma may find it difficult to help the Board better understand its invention.

It’s easy to see how anyone might have trouble understanding “phonons.” As patent practitioners, we owe it to our clients to patrol our Office actions and Board decisions to ensure that fact finding is accompanied by the kind of reasoned explanations demanded by law. It’s human nature to take short cuts. When an examiner or the Board does so at our client’s expense, fighting back is the only sensible response. And cases such as Rovalma provide ammunition. Sit vis nobiscum!

– Jonathan Schuchardt, Ph.D, JD

This article is for informational purposes, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and may be considered advertising under applicable state laws. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author only and are not necessarily shared by Dilworth IP, its other attorneys, agents, or staff, or its clients