Bad Grammar: Fed. Circuit’s Claim Construction Splits an Infinitive in Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera

Mar 30th, 2015 by Jon Schuchardt | News | Recent News & Articles |

My mother stood 4’ 10” tall, tipped the scales at 98 pounds, and was a stickler for correct grammar. She bristled when anyone uttered “I ain’t going,” “He’s taller than me,” or “Are youse goin’ down the shore this year?” And she would have agreed with Judge Newman (and me) that the majority erred in its March 16, 2015 ruling in Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera Corp. http://tinyurl.com/q6gfpbj

At issue was whether U.S. Pat. No. 5,449,767, originally assigned to Yale University and later asserted by Enzo and Yale, covers both direct and indirect detection of a “signaling moiety” or only indirect detection. If the claim included direct detection, Applera would infringe.

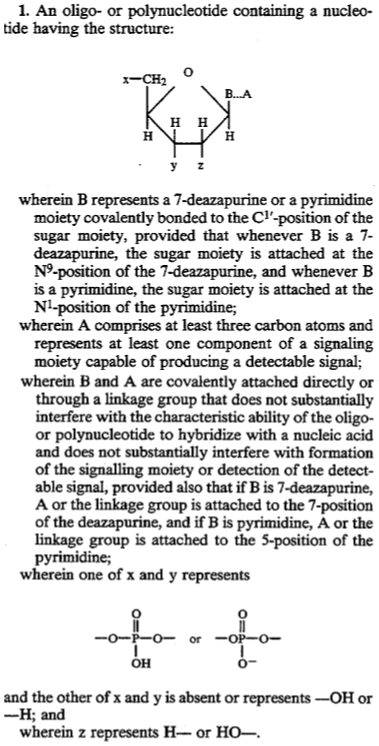

Claim 1 is reproduced below. In the structure, B is a purine or pyrimidine base, and A “comprises at least three carbon atoms and represents at least one component of a signaling moiety capable of producing a detectable signal.” A and B are “covalently attached directly or through a linkage group that does not substantially interfere with the characteristic ability of the oligo- or polynucleotide to hybridize with the nucleic acid and does not substantially interfere with formation of the signaling moiety or detection of the detectable signal . . . .” Notice that it is the linkage group that “does not substantially interfere.”

After hearing expert testimony, the district court found that “A . . . is one or more parts of the signaling moiety, which includes, in some instances, the whole signaling moiety.” Observing that at least one example in the patent could involve direct detection and that claim 67 recites “An oligo- or polynucleotide of claim 1 or 48 wherein A comprises an indicator molecule,” the district court concluded that there was “no basis for inferring from the word ‘comprise’ in certain claims that A must have more than one component, as opposed to suggesting that A may have more than one component” (emphasis in original). Consequently, the district court held that Applera infringed.

The Federal Circuit reversed. In an opinion by Chief Judge Prost, the court held (2-1) that the district court erred in construing the disputed terms of the patent to cover both direct and indirect detection. In doing so, the majority afforded no deference to the district court’s fact finding incident to claim construction, which is now required by Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 135 S.Ct. 831 (2015). Instead, the majority focused on the claim language and teachings in the specification to conclude that, as a matter of grammar, the signaling moiety must have more than just “A.”

The Federal Circuit reversed. In an opinion by Chief Judge Prost, the court held (2-1) that the district court erred in construing the disputed terms of the patent to cover both direct and indirect detection. In doing so, the majority afforded no deference to the district court’s fact finding incident to claim construction, which is now required by Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. v. Sandoz, Inc., 135 S.Ct. 831 (2015). Instead, the majority focused on the claim language and teachings in the specification to conclude that, as a matter of grammar, the signaling moiety must have more than just “A.”

The majority writes: “‘[A]t least one component of a signalling (sic) moiety’ indicates that the signalling moiety is composed of multiple parts as the term ‘component’ in and of itself indicates a multipart system. Thus, construing the phrase to allow for a single-component system, as the district court did here, would read out the phrase ‘component of a signalling moiety’ and would thus impermissibly broaden the claim.”

I disagree with the majority (and agree with the district court) because the mere fact that the signaling moiety could have multiple components does not preclude it from having A as its sole component.

The majority’s analysis in the first full paragraph on page 10 also misses the mark. The court writes: “if ‘A’ alone could be the signalling moiety, as the district court found, the requirement that ‘A’ not interfere with the formation of the signalling moiety would be read out of the claim, as the signalling moiety would be formed by the sole presence of ‘A’” (emphasis added). As I noted earlier, and as a “matter of grammar,” it is the linkage group, not “A,” that must not interfere in certain ways.

The majority says (p. 11, second full paragraph) that “the specification provides additional support that claim 1 covers only indirect detection.” Here, the majority cites to numerous places in the specification. However, these citations fail to support its point that “’A’ is described as being capable of forming a signalling moiety only in conjunction with other chemicals, never that ‘A’ alone can be a signalling moiety.” Instead, the cited passages consistently read: “A represents a moiety consisting of at least three carbon atoms which is capable of forming a detectable complex with a polypeptide . . . .”

The majority affords no deference to the district court, apparently relying on only the “plain language” of the claims and specification. On occasion (e.g., p. 13), the majority tap dances, suggesting that “even if” it were to consider the extrinsic evidence, it would not “override our analysis of the totality of the specification, which clearly indicates that the purpose of this invention was directed towards indirect detection, not direct detection.”

Judge Newman would have affirmed. She observed that this is the second time a Federal Circuit panel reviewed the same claims on appeal from the district court. In the prior case (Enzo Biochem Inc. v. Applera Corp., 599 F.3d 1325 (Fed. Cir. 2010)), Judges Michel, Plager, and Linn agreed with the lower court that A could refer to the “whole signaling moiety.”

“My colleagues err. The rules of grammar and linguistics, even in legal documents, do not establish that ‘at least one’ means two or more . . . The district court construed ‘at least one’ in accordance not only with grammatical logic, but also with the intrinsic and extrinsic evidence.”

According to Judge Newman, the district court’s factual findings were entitled to deference on appeal, consistent with Teva v. Sandoz. The district court’s determinations that “at least one component” could refer to the “whole signaling moiety” and that claims 67, 68, and 70 of the ‘767 patent “teach direct detection” were reversible only if clearly erroneous. “My colleagues show error of neither fact nor law in the court’s findings and conclusions.”

I vaguely recall a description for a high-school English course aimed at college-bound juniors and seniors and taught by a Ph.D. who seemed cut out of Shakespeare Magazine. In part, the description read: “Are you indiscriminately splitting your infinitives? Dangling your participles? . . . If so, this course is for you!” Daunted by the upper-level course, and unsure of what a split infinitive was or how to cure a dangling participle, I opted for a creative writing course instead. Although she never commented on my selection, I’m guessing my mother wasn’t happy.

– Jon Schuchardt

Check out Jon’s bio page

This article is for informational purposes, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and may be considered advertising under applicable state laws. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author only and are not necessarily shared by Dilworth IP, its other attorneys, agents, or staff, or its clients.