Obvious To Try My Patience: Federal Circuit’s Evolving Measure of Obviousness under 35 U.S.C. § 103

May 21st, 2014 by Jon Schuchardt | News | Recent News & Articles |

Nothing endures but change. –Heraclitus

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. –Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr

When I was your age, and Pluto was a planet, “obvious to try” was not the standard for evaluating patentability under 35 USC § 103. In KSR v. Teleflex, the US Supreme Court qualified this by rejecting the Federal Circuit’s “TSM” test in favor of a more flexible standard. Thereafter, a skilled person might respond to a “design need” or “market pressure” to solve a problem having only a “finite number of predictable solutions.” Such an application of “common sense” would be unpatentable and “obvious to try.” Perhaps your patience has also worn thin in considering the possibilities?

Recent Federal Circuit decisions continue to shape the law of obviousness and the meaning of “obvious to try.” Here are three examples:

1. Leo Pharmaceuticals v. Rea (Fed. Cir., August 12, 2013)

In Leo, the CAFC reversed a Board decision that held Leo’s patent obvious in an inter partes reexamination challenge. The invention related to a psoriasis treatment that combined a Vitamin D analog, a corticosteroid, and a non-aqueous solvent (polyether, fatty alcohol, or fatty ester). The prior art taught that Vitamin D treatments required high pH (8), while corticosteroids needed low pH (4-5). Consequently, physicians prescribed a two-drug regimen that suffered from poor patient compliance. In evaluating the art, the Board reasoned that the skilled person would have been able to choose what ingredients to include or exclude in formulating Vitamin D analogs and steroids.

“To the contrary,” wrote Chief Judge Rader, “the breadth of these choices and the numerous combinations indicate that these disclosures would not have rendered the claimed invention obvious to try.” Citing In re Cyclobenzaprine litigation: “where the prior art, at best gives only general guidance as to the particular form of the claimed invention or how to achieve it, relying on an obvious-to-try theory to support an obviousness finding is impermissible.” While the prior art had identified Vitamin D analogs and steroids as effective for treating psoriasis, “the same prior art gave no direction as to which of the many possible combination choices were likely to be successful.”

2. Sanofi-Aventis v. Glenmark (Fed. Cir., April 21, 2014)

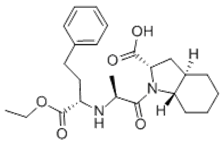

Generic drug maker Glenmark admitted infringement at trial but argued that Sanofi-Aventis’s patent (US 5,721,244) covering its Tarka® antihypertension drug (a combination of a calcium antagonist and trandalopril) was invalid under Section 103. The structure of trandalopril includes a bicyclic octahydroindole moiety:

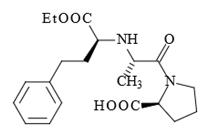

Prior art compositions used with calcium antagonists included otherwise structurally similar single-ring pyrrolidine analogs such as enalopril:

Glenmark urged that the district court erred as a matter of law because the combination of trandalopril and a calcium antagonist was “obvious to try.” In particular, Glenmark argued that because monocyclic inhibitors such as enalopril were known, it was obvious to try combinations of any calcium antagonist and any known ACE inhibitor, including trandalopril.

The ‘244 patent described the compounds and provided exemplary formulations, but it gave no performance results or any indication of advantages of the claimed compositions compared with known alternatives. As luck would have it, the compounds were eventually found to have advantages.

At trial, expert witnesses (not surprisingly) disagreed about whether it would have mattered to the skilled person to have one ring or two to fill the pocket of the ACE enzyme to inhibit its activity. The parties did not dispute that the claimed combination had longer-lasting effectiveness and improved kidney and blood vessel function that were not suggested by the prior art.

Nonetheless, Glenmark argued that the combination was unpatentable as a matter of law, and the patent owner’s later discovery or unexpected or advantageous properties could not be relied upon to demonstrate nonobviousness. “That is incorrect,” wrote Judge Newman, “patentability may consider all of the characteristics possessed by the claimed invention, whenever those characteristics become manifest.” Citing KSR, the court reminded us that “obvious to try” requires a “finite (and small in the context of the art) number of options” that are “easily traversed.”

3. Hoffmann LaRoche v. Apotex et al. (Fed. Cir., April 11, 2014)

The CAFC affirmed (2:1) a New Jersey district court’s summary judgment ruling that patents owned by Hoffmann-La Roche covering Boniva®, its once-a-month drug for treating osteoporosis, were invalid under 35 U.S.C. § 103. Ibandronate, a bisphosphonate, was approved by the FDA in 2005. After generic drug manufacturers submitted ANDAs to the FDA seeking approval to manufacture ibandronate prior to expiration of the patents, Roche sued for infringement.

Despite Roche’s arguments that a once-monthly 150-mg dose of ibandronate provided an unexpected improvement in bioavailability of the drug compared with the usual 2.5-mg daily dose, the district court concluded that once-a-month dosing of ibandronate was established in the prior art, and that a combination of references suggested that the 150-mg monthly dose was “obvious to try.” The lower court ruled that Roche’s bioavailability argument, which was raised for the first time at oral argument, “does not rise to the level of a mere scintilla, and it is not sufficient to defeat the motion for summary judgment.”

The Federal Circuit agreed that a monthly 150-mg dose was obvious. It cited trade journal articles and earlier patents that described monthly dosing of bisphosphonates, including ibandronate, as a solution for poor patient compliance with daily regimens. The court found a 2001 article by Riis on intermittent versus daily dosages persuasive. Riis concluded that “it is the total dose over a predefined period and not the dosing regimens that is the determining factor for effect on bone mass and architecture after ibandronate treatment.” After considering Riss and references that taught to use 5 mg per day or 35 mg per week, the court concluded that a monthly 150 mg dose was at the very least “obvious to try,” and there was a reasonable expectation of success in treating osteoporosis with the once-a-month 150-mg dose. The court also dismissed Roche’s argument that the art suggested adverse gastrointestinal side effects of higher doses of bisphosphonates. While the bioavailability argument had some appeal, the majority considered it insufficient to “rebut the strong showing that the prior art disclosed monthly dosing and that there was a reason to set the dose at 150 mg.”

Judge Newman’s patience was obviously “tried” because she posted a stinging dissent. The ruling “violates the principles of Graham v. John Deere Co. . . . (all factors must be considered) . . . violates the guidance of KSR . . . (the standard of obvious-to-try requires a limited number of specified alternatives offering a likelihood of success in light of the prior art and common sense)” and invokes “hindsight to reconstruct the patented subject matter.” Judge Newman remarked that the FDA “refused to approve the 5 mg dose due to its toxic effects. Surely this leads away from the obviousness of a single dose thirty times larger.” She disposed of key references and criticized the majority’s reliance on the Riis study: “Riis makes no suggestion that the once-a-month dosing at the high dosage used by Roche could replace Riis’ elaborate procedure.” The evidence of long-felt need, failure of others, and commercial success provided by Roche was “unrebutted” by the challengers’ experts. “Their only argument was that it would have been “obvious to try” the Roche method. “The extensive experimentation with other regimens and dosages demonstrates that this selection was not obvious to try.”

Predictably, in the post-KSR world, district courts struggle with what it means to be “obvious to try.” However, as the cases discussed above demonstrate, even the Federal Circuit judges still disagree about what is “obvious to try” and therefore unpatentable. Like our definition of “planet,” the law of obviousness evolves, and the only thing we can be sure of (aside from death and taxes) is that change endures.

– Jon Schuchardt

Check out Jon’s bio page

This article is for informational purposes, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and may be considered advertising under applicable state laws. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author only and are not necessarily shared by Dilworth IP, its other attorneys, agents, or staff, or its clients.