From A[pple] to Z[eroclick]: The Federal Circuit Overrules District Court in Zeroclick, LLC v. Apple, Inc.

Jun 11th, 2018 by William Reid | Patent Related Court Rulings | Patent Trends & Activity | Recent News & Articles |

In Zeroclick, LLC v. Apple Inc., 2017-1267 (Fed. Cir. June 1, 2018), the Federal Circuit overruled the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California for improperly interpreting claims regarding the application of 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶ 6. The case related to an appeal from an action where Zeroclick had sued Apple for infringement of claims 2 and 52 of U.S. Patent No. 7,818,691 (‘691 Patent) and claim 19 of U.S. Patent No. 8,549,443 (‘443 Patent). The district court had found the claims invalid as being indefinite.[1] The court had construed the claims as reciting means-plus-function elements but did not find correspondingly sufficient structure in the specification.[2]

In Zeroclick, LLC v. Apple Inc., 2017-1267 (Fed. Cir. June 1, 2018), the Federal Circuit overruled the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California for improperly interpreting claims regarding the application of 35 U.S.C. §112, ¶ 6. The case related to an appeal from an action where Zeroclick had sued Apple for infringement of claims 2 and 52 of U.S. Patent No. 7,818,691 (‘691 Patent) and claim 19 of U.S. Patent No. 8,549,443 (‘443 Patent). The district court had found the claims invalid as being indefinite.[1] The court had construed the claims as reciting means-plus-function elements but did not find correspondingly sufficient structure in the specification.[2]

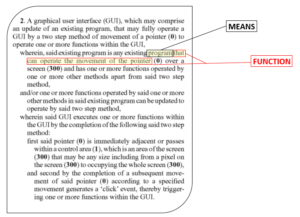

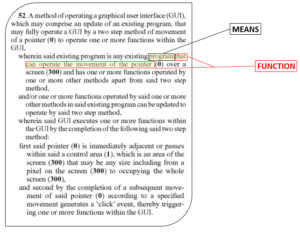

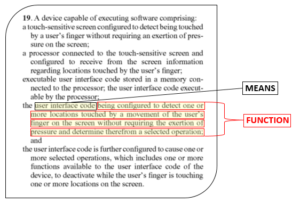

The patents themselves relate to modifications of graphical user interfaces for computers and cell phones. The key issue for the Federal Circuit was the propriety of construing the terms “program” and “user interface code” as means for performing functions. The relevant claims are shown in the inserts below with the purported means and functions highlighted.

Claims 2 and 52 of the ‘691 Patent

The Federal Circuit began its analysis by noting that there is a rebuttable assumption that when the word “means” is missing from a claim, §112, ¶ 6, doesn’t apply.[3] Rejecting the district court’s analysis, the Federal Circuit found that legal error occurred when the district court ignored this unrebutted presumption and treated the terms “program” and “user interface code” as nonce words, which can in some circumstances be the equivalent of the word “means.”[4] The Federal Circuit pointed out three problems with the district court’s analysis. First, the mere existence of functional language doesn’t automatically convert words into means for performing the function.[5] Second, the district court did not analyze the words in context where there was clear support as to their plain and ordinary meaning.[6] Finally, the district court made no showing that the graphical user interface or code were typically used as a substitute for the word “means.”[7]

In this case, the Federal Circuit applied well-known claim construction rules regarding §112, ¶ 6, and avoided clouding the waters with caveats, as advocated by Apple.

This article is for informational purposes, is not intended to constitute legal advice, and may be considered advertising under applicable state laws. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author only and are not necessarily shared by Dilworth IP, its other attorneys, agents, or staff, or its clients.